How Does Mental Health Impact Immigrants In Schools?

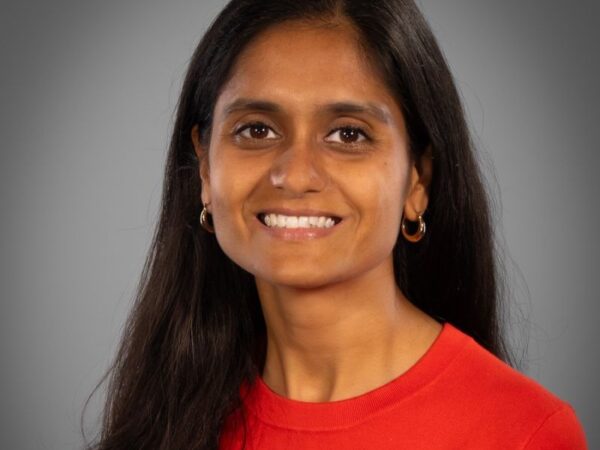

Dr. Sara Castro-Olivo moved to the United States from El Salvador at 14 years old where she enrolled in high school. Her American public school experiences, and those of her classmates, helped shape her future studies and career.

Castro-Olivo and a group of seven other immigrant girls started school in California together. By their junior year, six had dropped out. Only two graduated high school and Castro-Olivo was the only one to go to college. She started to question what was happening. She could not understand how such smart and dedicated girls could give up on their dreams.

“They aspired to go to college. They had done really well in their countries of origin. Brains were not the reason they quit on school.”

She quickly found her friends were not alone. Studies have shown that up to 80 percent of Latinos who come to the U.S. as middle or high school students do not graduate high school.

Castro-Olivo’s research kept pointing back to the lack of school belonging and perceived discrimination. She noticed different factors that contributed to a failure to graduate despite the motivations and aspirations to do so.

Those findings prompted her to look into what can be done in our schools to ensure proper mental health services are provided. She focused on culturally responsive social-emotional and behavioral interventions, mainly for Spanish-speaking immigrants or refugees children and families.

“Like any other child, they are developing and trying to figure out life. By itself, puberty and adolescence is stressful and causes anxiety and depression,” explained Castro-Olivo, associate professor in educational psychology. “On top of age-related complexities, immigrant children and adolescents are having to adapt to a new culture; a culture that many times can be conflicting or have conflicting values than their own. Views of the world can be different from home and school. Many times, the children don’t know how to bridge these gaps and they need more support to cope with everything.”

Identifying Interventions

According to the latest Census Bureau report, 39 percent of people in the U.S. identify as a racial/ethnic minority. That number is even higher among school-aged populations.

Many teachers and administrators struggle to identify effective interventions for children who come from diverse cultural and language backgrounds.

Even if we are bilingual or bicultural, we’ve studied theories and practiced in the United States so we’re coming from a different cultural angle than the parents are. We need to learn how to make the theories we are learning in our teacher or psychologist training programs more culturally responsive or learn ways to better align them to the cultural realities of the populations we serve.”

Research has shown that culturally and linguistically diverse students are more likely to struggle with mental health problems. They sometimes face discrimination from teachers and peers and they feel like they do not belong in school while also feeling like they cannot communicate freely about their feelings.

“Many times, teachers forget the huge emotional loads these kids are carrying in their ‘backpacks’. When I say backpacks, I really don’t mean the ones full of books, but full of a lot of baggage they pick up in their road to acculturation. It’s really difficult to teach kids when they’re carrying so much.”

For Castro-Olivo, it is about setting aside biases and focusing on the students’ cultural realities. She is not suggesting every teacher or administrator become a mental health care professional, but be more aware of struggles students are facing.

“It goes beyond what we do in the classroom through the basic academics. It’s important for us to start to realize that we’re not going to help these kids just by teaching them how to read and write and do math. If they don’t have the social-emotional support in their schools and schools don’t do a better job of helping parents see how they can support that part of their development better from home, then whatever we do academically is not going to make the difference we want to see.”

Project F.U.E.R.S.A.S.

To help immigrant and refugee students with many of the struggles they face, Castro-Olivo and her colleagues created Project F.U.E.R.S.A.S.: Facilitating Universal Resiliency for the Social and Academic Success of Latino ELLs and families.

As part of Project F.U.E.R.S.A.S, students are taught basic social-emotional learning skills; things like self-awareness, social awareness, empathy, anger management and decision making in a culturally responsive manner. This allows them to see how they can use these skills in their daily lives as they adapt to their life in the U.S.

The program has proven to be effective in improving resiliency among these students, so much so that parents asked for their own component.

The parent component of Project F.U.E.R.S.A.S focuses on many of the same elements taught to the students. Parents are equipped to help at home but the program also integrates ways parents can be more involved in their child’s education and have a better understanding of the educational system.

“We do this in a very sensitive way so they don’t feel like we’re criticizing their parenting,” said Castro-Olivo. “We aren’t trying to change something that they believe in because that’s what they grew up with. We just like to share with them the reality of our school systems and the limitations teachers could have to support, and sometimes even discipline, their children if there is no home-school communication. Parents tend to be very intimidated to communicate with their children teachers. We work hard to break those barriers and help immigrant children and families succeed socially, emotionally and academically.”

About the Writer

Ashley is the Media Relations Coordinator and responsible for news coverage in the Department of Teaching, Learning and Culture as well as the Department of Educational Psychology.

Articles by AshleyFor media inquiries, contact Ashley Green.

Fundraising

To learn more about how you can assist in fundraising, contact Amy Hurley, Director of Development ahurley@txamfoundation.com or 979-847-9455